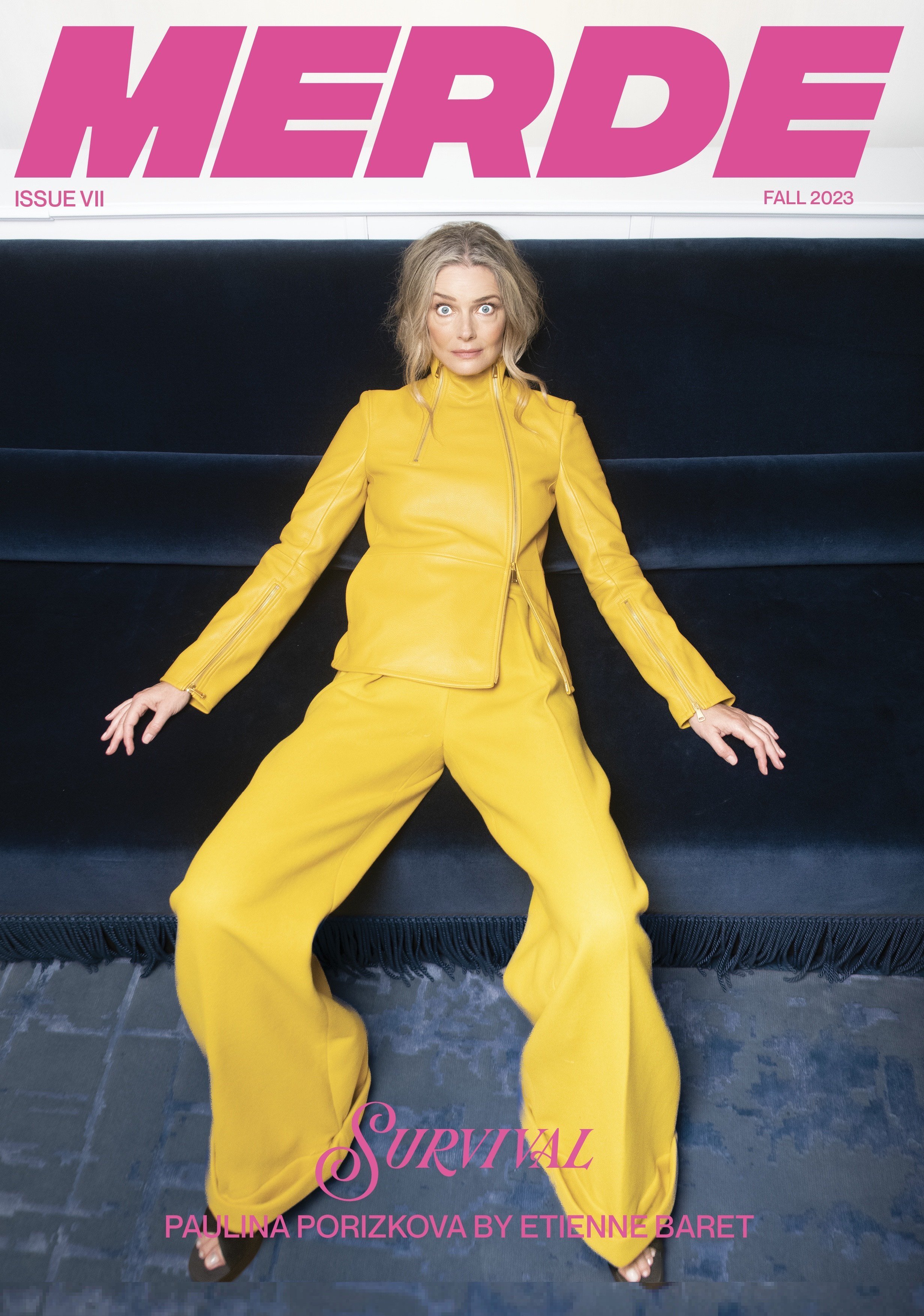

Paulina Porizkova for the Cover of MERDE 7: Survival

Photographe: Etienne Baret

Styliste: Justine Bleicher

Makeup: Marie Trisch

Hair: Adrien Tavolieri

Paulina Porizkova speaks to Etienne Baret with no filter. For decades, she made her name as an international supermodel gracing the covers of Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Sports Illustrated, Cosmopolitan, and many many more. Now her image has been augmented by her own voice thanks in part to her book No Filter: The Good, The Bad, and The Beautiful (The Open Field, 2022). She writes openly about her life shifting upside down more than once. The author, originally from former Czechoslovakia, spent her childhood as an outsider in Sweden facing the social scrutiny of adolescent cruelty and a broken home. Fast forward more than forty years, Paulina is once again ostracized, this time for being the woman openly crying on social media. Paulina and Etienne are both out to revolutionize the system, and Etienne’s lens becomes another door allowing Paulina to do so. Step aside ageism and shame—Paulina is here to flip the narrative and lead us into an open, unfiltered future.

Etienne: I wanted to start by saying that today is a very important day for me, Because this is my first editorial interview. I'm so lucky to be able to do it with MERDE. My friends told me ‘MERDE luck!”

Paulina : The title MERDE is a bit provocative, and that’s such a good part of life, to poke a little bit, because that's how new thought is born. I mean, otherwise we all just like repeating the same answers to the same questions.

Etienne: I want to speak first about the chapter in your book ‘No Filter’ titled ‘Chimneys.’ So this chapter touched me a lot, and I actually read it in the countryside while I was literally in front of a chimney. I deconstructed what you wrote about the analogy of using the Chimney as a way into love. The chimney is the dirtiest way to get into the house, you’ll be covered in soot no matter what, though it's still a way in. It embodies both life and death, because it burns wood to make a fire, which brings warmth, light and often a cooked meal. It becomes an allegorical element of life in the home. I felt this chapter in no filter connected to MERDE Issue 3 editor’s letter, in which Molly wrote, “In the context of past confinement, my goal became to embrace the shit, making it work to my advantage, rather than dodge its backsplash. In this way, MERDE Magazine adapts alongside life’s shit, sticking to our founding principles, away from the typical and towards the unexpected.

Dress LOUIS VUITTON

While the Chimney is the most difficult and dirty way to enter the house, this dirt and shoot represent the result of living life in this house, the life in our bodies. I think a house with a sootless chimney is a dead house.

Paulina: It’s an empty house.

Etienne: Yes, exactly. I think we need to embrace the shit, as Molly wrote, to keep moving forward. We need to go through chimneys and get dirty because that’s life.

Paulina: First of all, thank you for the kind words. I know exactly what you speak. Mirroring, I think that being able to find little pieces of yourself in somebody else is what builds the connections between humans. In a way, when I was writing the book, that’s what I was trying to do, because I was so lonely and sad. I needed to reach out. I wondered if there was somebody out there that could mirror me, and I couldn’t find that at the time. When I was writing, I was in part hoping that someone would find in me what I wanted to find. That mirroring concept, it’s being heard, when someone validates your experiences and emotions that you might have felt really lonely with. When you see someone talk about their experiences that are so similar to yours you feel ‘oh, I’m not the only person in the world, I don’t have to feel so lonely, someone else gets it.’ That connection between humans is what life is all about, we can’t exist without that. We always look for it, that’s why we create art. That’s why we consume art, to connect.

Etienne: It's funny because reading your book I had this very warm yet strange and distributing feeling of the fact that you wrote this book for me.

Paulina: What an honor, I think that’s the nicest compliment I’ve gotten on the book. That hits me, thank you.

Etienne: It was an incredible experience to read it.

Paulina: When you were describing the house with the chimney, with the soot, it reminded me of the vagina. The vaginal canal, and a baby coming out, not in a clean way, but into the world and into presumably and hopefully, love, which obviously doesn’t always happen. The chimney is the most symbolic of all the entrances into the house that is love. It’s interesting to you related to that chimney itself. It’s very female, isn’t it? The chimney.

Etienne: I think so, and maybe the baby being born is the first chimney of your life.

Paulina: It seems to be, then hopefully if you come into the right house, somebody will show you the front door entrance into love so you don’t have to struggle so much every time you need some love. For some of us, it’ll be the chimney forever.

Etienne: It’s disturbing, in a good way. I tried to remember when the first memory of survival was for me. The first notion for me, and I know you had the same experience you wrote about in your book, was having a panic attack as a child. Despite knowing much more now, when it’s happening, it’s the sensation of dying that’s not really rational. I think I experience and approach these attacks differently since reading your book, with more acceptance and letting go. I try to apply this approach in many situations, even not related to panic attacks and it working.

Paulina: You make me feel so wise!

Etienne: It’s amazing in a way, because it doesn’t change the experience, it changes what you take from the experience.

Paulina: It changes how you experience it. The experience is still the same, the pain, the fear, the inability to breathe. The lack of control, and the fear of lack of control is still there, but I think being able to sink into it – I’m still working on trying to welcome it, as in opening the door and going ‘come on, take me, do your worst.’ It’s hard, but I’m getting better at it, and it gets easier.

Etienne: How is a panic attack at 58 years old versus when you were 10?

Paulina: When it first starts happening and you don’t know what’s going on, and you’re a child, the thing to me that was the most prevalent was the fear of death. When I was a child, everytime I had one I thought I was dying, which made it much worse of course. That is not a pleasant feeling. I wrote about the first attack I ever had in my book at 10 years old, at my father’s house who I barely knew. I crawled to the bathroom and I spent most of the night on the bathroom floor hugging myself and crying. I didn’t dare wake my father up because I thought, in typical child fashion, the anxiety attack was me going to die and that was somehow my fault. That I was bad, for being inadequate, like I was a faulty child - so just in case I didn’t die, I didn’t want anyone to know how faulty I was, that I was broke, or not worth having. Do you remember your first?

Etienne: Yes, I have the emotional memory of the attacks as a child and a teenager as shame. I was trying to hide it.

Paulina: Exactly, you don’t want to show what is wrong with you.

Etienne: I remember one day in college I had one in the cafeteria and that was horrible, I remember how cruel one can be at this age. I remember everyone looking at me like a freak. It’s a kind of trauma, you carry it with you even if you can analyze and detach from the shame as an adult. It’s okay to be not okay, as you say.

Paulina: I think we’re both very acquainted with shame, feeling like there was something wrong with us and that’s why we couldn’t be loved the way that a child should be loved, and It was our fault. I couldn’t figure out why, and I know you couldn’t figure out why either, right? That’s an enormous amount of shame for a child to have to bear, to feel like you’re not worthy of love because there’s something wrong with you, you came out of the factory wrong. Somebody forgot to install something important in you that makes you not as good.

Etienne: Exactly, and you can’t do anything about it.

Paulina: You just try to hide it so people don’t find out. I think that’s why I’m so busy putting all of myself out there, so I don’t have to suffer that shame anymore. Giving away my secrets, gives up my shame. How do your panic attacks differ today from the ones you suffered as a child? I can say that mine have gotten tolerable. When they come, I can say ‘oh hello there,’ kind of like when someone knocks on your door you don’t really want to see but you can’t get rid of them so you’re like ‘alright hey, how are you doing, nice to see you, okay… okay… okay… talk to you later.’ It’s not coming in to kill you, it’s there to annoy you. It’s easier to know you’ll be able to shut the door on it, because you’re not going to end up dead. You just lose a little bit of time.

Dress, Earrings and Necklace CHANEL

Etienne: Well, I think now, having people around me who know and accept me, It’s changed the attacks very much. When I’ve had my more recent panic attacks, I’ve been with people who love me and people I love, so it was okay, it was a secure space. It’s like getting naked, it’s more than naked, it’s indescribable.

Paulina: It’s more like you’re opening up your ribcage, and people get to dip their fingers into it. To me, naked, as you know, is a position of power, if it’s my choice.

Etienne: But this is not a choice. I think now, I still feel the sensation of losing control, but it’s more rational and I know it’s not the end. You know it’s going to end, and after it’s going to be ok. I try not to resist, and now when I get a panic attack I lay on the ground on my back - which is actually the position of dead people *laughs* and try to accept it. I also don’t try to escape to another room or hide it if I’m with people, I just try to concentrate on what is happening, they are my family, they are my friends, I’m just having a fucking panic attack and it’s going to be done in four minutes. I try not to dwell on the way I look, which is ridiculous when you think about it, but I always thought about it.

Paulina: The last panic attack I had was last week when my boyfriend and I were traveling all over Europe and it was craziness. I was in a taxi on my way to the train station in London. I always carry a fan with me, one of these old fashioned fans, it somehow helps with the rhythmic movement and the wind. I just turned to my boyfriend and said ‘I’m having a panic attack’ and he said ‘is there anything I can do’ and I said ‘nope.’ I’ve talked to him before, what I need when I’m having one, is just to bear with me, just give me the space to do whatever the fuck I need. If I need to cry, sweat, whatever it is I need, just leave me to it, let me know that you’re there, but not impose so I don’t have to try to entertain you. 15 minutes later, it evaporated and I was fine. Little bastards those things.

Etienne: What is an element of survival that you feel lives in your guts?

Paulina: That’s a big question, that feeds off the feeling that you might die in a panic attack, but survival, actual survival, is about biological imperatives, but also the true things that I talk about in my book because I really truly believe that hope should be a biological imperative, because without hope, you will die.

Dress MAISON RABIH KAYROUZ

Etienne: I think the greatest things accomplished by society have been led by hope. Hope is why we’re still here. Hope is life.

Paulina: A lot of survival is courage, maybe the courage to have hope when it seems hopeless.

Etienne: Surviving is in a sense a misinterpretation, because the word can evoke two contradictory ideas. It can evoke first the idea of living a diminished and precarious existence, as if you’re reduced to only your biological functions. In a way it’s living less. The second idea is living a reinforced way, to live stronger, and more resilient - living more. Which notion of survival do you resonate with, living less, or living more?

Paulina: That’s such an interesting take, I’ve never thought of this this way. Is survival just getting by, or is it conquering or overpowering. Survival is something that I’ve tagged along with me emotionally, not physically, since I think I even developed a conscious mind - the possibility of dying. In terms of my own existence, will I make it, will I be here, and for how long? That’s where the panic attacks come in and tell me, maybe this is it for me. What does it mean for you?

Etienne: In my reflection, I don’t really have an answer. It depends on one’s point of view, and one’s experiences of surviving. When I had the literal feelings of surviving as a child I approached the idea as living less, getting by. Feeling really weak and handling each situation as they came. Looking back now, which I still analyze as surviving times of my life, I now feel I found strength in these moments.

Paulina: See that’s interesting, I write about this in the book - the old clique ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.’ We’re going on the premise that if it doesn’t kill you, it will strengthen you.’ It’s not true, it’s not actually true. I read in a medical journal, that when you are exposed to situations, both emotional or physical, that are too hard to bear, they usually kill you - they can diminish you emotionally or physically, but what doesn’t kill you, most of the time actually kills you.’

Etienne: What didn’t kill me, slapped me.

Paulina: Exactly! It still punched you.

Etienne: The only good thing I found in these moments is making decisions.

Paulina: That, and how to deal with getting punched. And also, how many times can you get punched, and how many punches can you take, because it’s a good thing to know. It’s not that ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger’ it’s that ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you understand how strong you already are,’ how much you can actually carry. Being tested by moments of survival, you find out how much you can take. This is the wonderful thing about getting older, you can assess better how much you can handle and what are your limits. It’s a fabulous thing to know.

Etienne: Everything is related. Generally, I don’t try to find answers, just keep asking questions.

Paulina: That’s a very mature way of looking at things, to constantly look for questions and find out different ways of asking them. I like answers, binary, zeros and ones. I want to find answers, but that’s the quest in life - finding the answers is the fun bit.

Etienne: In No Filter, there are more questions than answers.

Paulina: I hope so. Because I don’t have any fucking answers. That is the one answer I do have. Anybody that tells you differently is full of shit.

Etienne: Finally, I want to discuss the big subject of time. You regularly raise the issue of agism, and I wonder whether you think botox and cosmetic surgery is ultimately a form of survival? In terms of surviving time. Or is it the opposite? It is not defying yourself, accepting the passage of time, the aesthetic degeneration of your body, is this surviving the society we live in?

Paulina: That's an excellent question - and it leads me back to living for battle or living to accept, which is the better living? Some people like the battle, they’re energized by it. Taking your wrinkles away, smoothing out your skin is battling with visible age. You are not willing to accept that you’re getting older, or let other people know you’re getting older. You’re going to battle with age. You will die one day, regardless of how much botox you’ve had. Ultimately, death waits for us all, and you can choose to pretend and battle, but death is going to win anyway. Or you can choose to accept age, which I believe would free up a lot of precious time, time to do things that are a little more pleasant than injecting your face, maybe, for some of us. For some of us, battling the signs of age is a purpose in life, not to give in. Are you going to battle or are you going to accept? I think it’s an individual choice, I’m not looking down on either of the choices, I just get to make my own choice and at the moment, I’m mostly trying for acceptance with small particles of ‘no fuck this, I still want to be in the game’